Domestic violence legislation in Kazakhstan and across the world

On April 15, Head of State Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, signed a law harshening punishment for domestic violence and other crimes related to women and children. Commonly known as Saltanat’s Law in honor of Saltanat Nukenova, who in November of 2023 was murdered by her husband and ex-minister of уconomy of Kazakhstan, Kuandyk Bishimbayev. Kazinform News Agency correspondent looks into the changes and policies related to domestic violence in Kazakhstan and around the world.

Now the murder of a minor, a child under 14 years of age, is punishable by life imprisonment instead of up to twenty years in prison. Pedophilia also carries a life sentence. For harassment of a sexual nature to children under 16 years of age, a fine of up to 200 MCI (738 400 tenge or $1 671,72 in 2024), 200 hours of community service or 40 days of arrest is imposed.

For the intentional infliction of moderate harm to health there is no restriction of freedom and the punishment can range from 2 to 3 years. Intentional infliction of minor harm to health entails punishment with the minimum penalty of 200 MCI (738 400 tenge or $1 671,72 in 2024), and the maximum is restriction or imprisonment for up to 2 years.

Battery was moved to the Criminal Code after seven years from the Code of Administrative Offenses. For beatings or committing other violent acts that caused physical pain, but did not cause minor harm to health, the minimum penalty is 80 MCI (295 360 tenge or $668,69 in 2024), and the maximum penalty is 100 – 200 MCI (369 200 – 738 400 tenge or $835,86 – $1 671,72 in 2024) or community service from 100 to 200 hours or arrest for up to 50 days. Currently, the offense is defined not as systematic battery, but as ‘violent acts committed with particular cruelty, bullying with the aim of causing suffering to the victim’. The maximum term of imprisonment is from 4 to 7 years.

The Committee on Legal Statistics and Special Accounts of the General Prosecutor's Office of the Republic of Kazakhstan reported that a little over 47 000 administrative cases were registered in 2023, in contrast to approximately 24 000 in 2018. In addition, the number of victims of intentional infliction of minor harm to health at home increased, amounting to about 20 800 in 2023 compared to approximately 15 500 in 2018.

Domestic violence law and regulations in other countries

In Tajikistan punishments for battery is a fine from 20 basic calculation indicator to 100 hours of community labor; intentional infliction of great harm to health is imprisonment of 5 to 15 years; torture – fine of 50 basic calculation indicator up to 5 year imprisonment; murder – 10 to lifetime imprisonment.

Cultural aspects play a huge role in the outcome of statistics of domestic violence inflicted on women in Tajikistan, which varies from 50% to 80% of women in the country. Gender-based stereotypes and patriarchal mindset lead to bigger problems like financial dependency and lower ratings of educational levels for women, also creating an environment of not recognizing the issues of violence on women as criminal. Domestic violence is not criminalized in Tajikistan and is seen as ‘domestic matter’ once again due to the traditional values. The first law on ‘prevention of domestic violence’ was adopted in 2013, however the police often avoid intervening in cases of domestic violence or accuse women of abusing them and sometimes abuse women who try to report abuse. There is also a lack of training when it comes to domestic violence cases among authorities and health care providers.

According to Kyrgyzstan's law battery is punishable by 200 calculation indicator or up to 100 hours of community labor; intentional infliction of great harm to health – imprisonment of 3 to 10 years; torture – correctional labor of 1 year up to imprisonment up to 8 years; murder – imprisonment of 8 years to lifetime.

According to the Central Asian Bureau of Analytical Reporting, in 2020 the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kyrgyzstan revealed that 6,145 cases of domestic abuse and the corresponding number of protection orders were reported in 2019 and 8,159 domestic violence offenses were reported nationwide in 2019. Of them, 560 in legal processes, 7045 terminated, and 554 sent to court. The statistics show that even with the domestic violence law adopted in Kyrgyzstan in 2017 and later implemented changes, a lot of women either do not report cases of domestic violence. Also, terminating the case before it goes to court is a common practice whether motivated by the pressure or lack of actual protection of domestic violence victims by the authorities.

In Sweden, one of the top 3 of the best countries for women in 2024, an abusive husband can be jailed for up to two years for beating his wife. Even if the woman filed a complaint and reconciled with her husband, the criminal case will still be investigated and brought to trial. In comparison with Central Asia or CIS, domestic violence in Sweden is treated as a public matter, not a private one. Twenty-five years ago, the Woman’s Personal Privacy Law was adopted in this country. Punishable acts include physical violence, psychological violence and financial pressure on the wife. However, even the best countries fail, especially with the global rise of domestic violence cases during, after and due to COVID-19 pandemic. Countries like Sweden faced issues of rising domestic violence on women and children.

In 2020 with the rise of cases of domestic violence against women during lockdowns, Secretary-General of the UN, addressed the issue and ‘urged governments to put women’s safety first’ calling for ‘ceasefire’ of domestic violence.

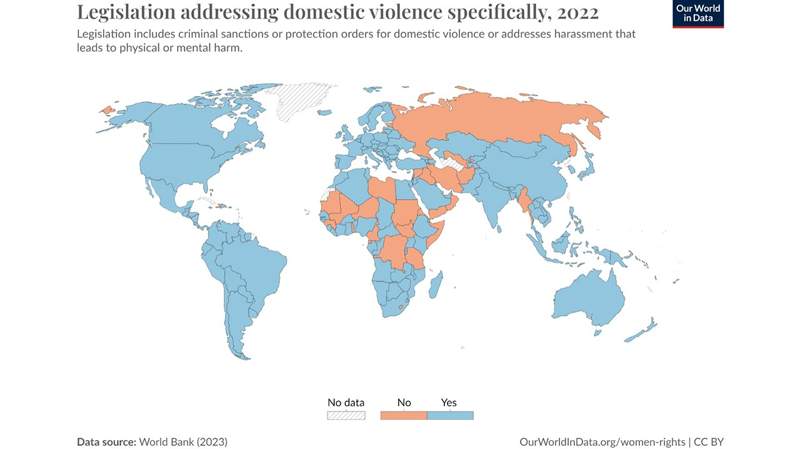

No domestic violence law

As most of the countries in the world start the process of criminalization or at least management of domestic violence on some level, there are those who have no legislation addressing the issue of domestic violence. Countries without any domestic violence protection include Russia, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Mauritania, Mali, Guinea, Cameroon, Congo, Tanzania, Somalia, Yemen and Oman.

There are several reasons why domestic violence laws are absent in these countries, some of the most important ones being taboos, cultural views, and religious beliefs. For instance, it is frowned upon for women to report any kind of assault they may encounter in Middle Eastern nations. Furthermore, due to unsuitable support from communities, the absence of documented occurrences makes it challenging to enact laws prohibiting domestic violence. There is no common law on domestic violence, hence these laws may also differ from one municipality to the next. Even legislation addressing domestic violence is opposed by many officials in these locations.

Global changes

In 2017, Tunisia made a major contribution to the worldwide movement against gender-based violence by passing comprehensive laws intended to reduce violence against women. One of the most notable aspects of this legislative revamp was the removal of a controversial legislation that had previously permitted rapists to avoid punishment by marrying their victims. Building on Tunisia's groundbreaking decision, Jordan and Lebanon moved quickly to remove their own antiquated "rape marriage" rules. In the meanwhile, Liberia has made significant progress in recent years in providing protection for victims of domestic abuse, as seen by the passing of many laws meant to strengthen safeguards for victims of intimate partner abuse.

Most of the countries have recent developments in their legislation addressing domestic violence (as recent as 2022-2024), including Kazakhstan. Nevertheless, despite the issue standing and numbers rising, more and more countries are starting to face the problem and take action against it towards change.